Recently, we’ve had patients asking about a procedure called “dry needling.” In this review we have attempted to explain this relatively new method for the management of musculoskeletal pain. Different methods of dry needling are examined, including effectiveness and potential benefits for those patients suffering from acute or chronic pain and sore muscles, as well as potential adverse effects.

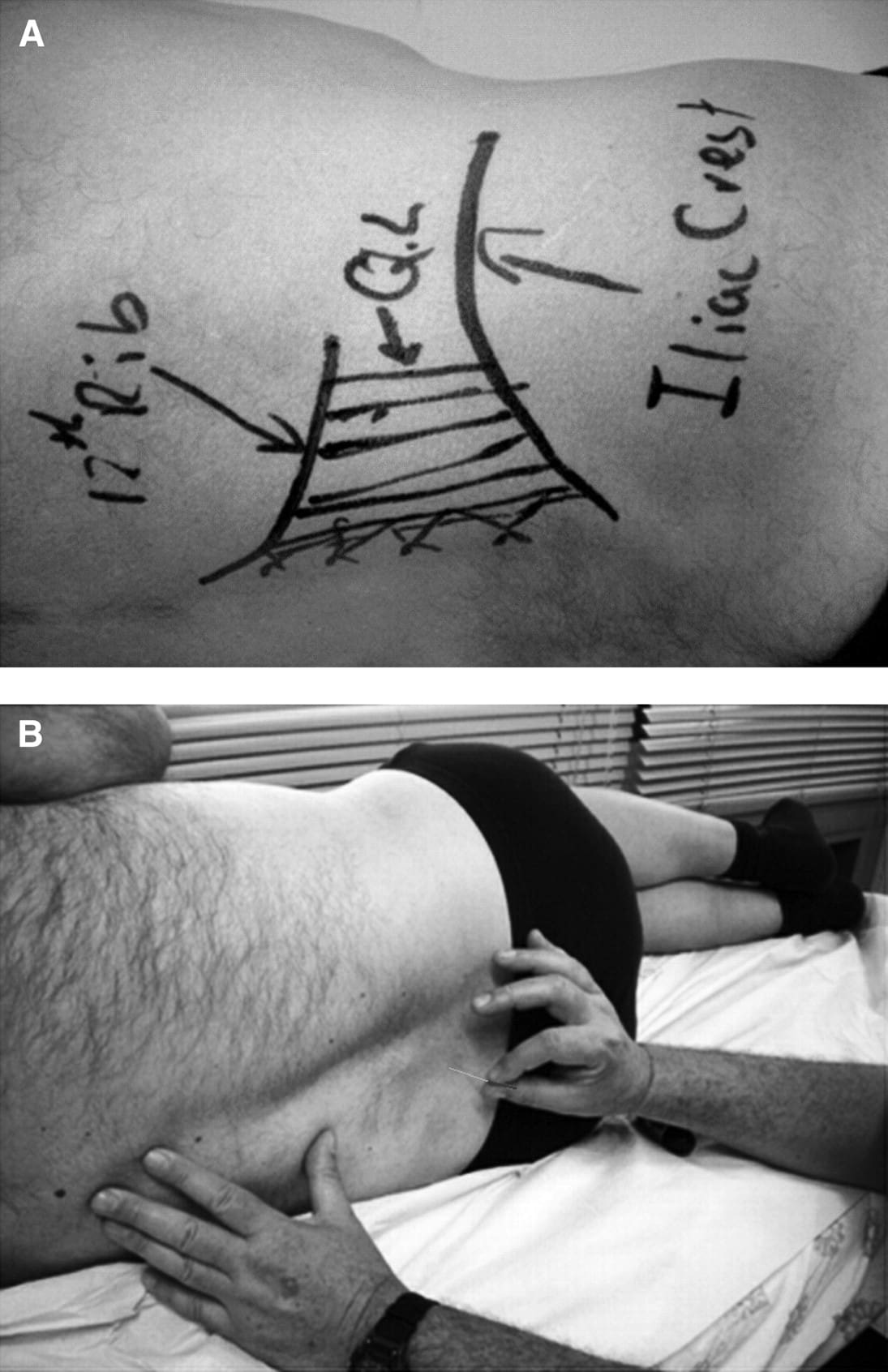

Examples of dry needling applications. A: Marking out the quadratus lumborum muscle before needling. B: Needling the paraspinal muscles.

The needles used in this procedure are very thin, and there is no solution injected (hence, “dry needling”). In fact, most patients fail to recognize when there is the actual insertion of the needle if there is no stimulation of the pain centers. A practitioner will insert the needle into the muscle with the aim of locating “trigger points.” Trigger points can be thought of as the source of the muscle pain, which will then radiate out to the surrounding muscle area. By inserting the needle into the trigger point, the practitioner wants to engage the trigger point. Engaging the trigger point will hopefully deactivate these pain centers. While it is possible for patients to gain immediate relief from the technique, most patients receive most benefit through a series of treatments over several weeks.Dry needling consists of the insertion of a filament needle into muscles that are identified as causing the patient pain. According to Kalichman and Vulfsons (2010), dry needling is “minimally invasive, cheap . . . [treatment that] carries a low risk.” A common misconception is that dry needling and acupuncture are identical procedures. While there are similarities, dry needling is not another name for acupuncture. Acupuncture therapy relies on traditional Chinese healing concepts of Qi and meridians; dry needling is a Western approach to pain management.

If the needle does engage a trigger point, the patient may experience a sudden, localized pain, which may feel to the patient like a muscle cramp–the severity of which will vary from patient to patient, depending on the patient’s pain tolerance and the underlying condition. In addition to the associated pain of the treatment, dry needling, much like any medical treatment, has associated risks. One such risk is related to the location of the musculoskeletal pain, which can present challenges in treatment. For example, if the pain is close to an organ, the practitioner must demonstrate care so as not to insert the needle into the organ. Studies have also noted patient complaints of soreness, local hemorrhages, muscle damage and passing out.

Patients desiring pain relief may benefit from dry needling. Before seeking treatment, the patient must be aware of the qualifications and licensure of the practitioner and the potential complications from the practice. If the patient does proceed with treatment, communication of symptoms and pains must be accurate and thorough so that the dry needling can produce the best outcome.

Sources